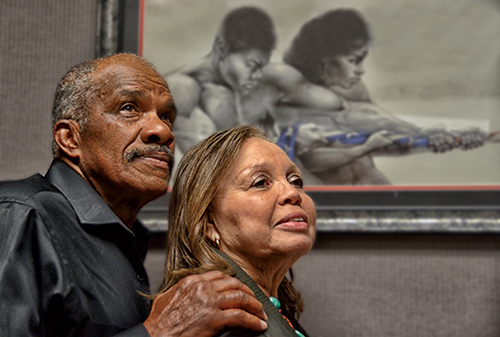

John & Jean Lewis remain active in the civil rights movement and the celebration of Dr. Martin Luther King’s birthday. Jean is president of the local NAACP chapter.

Written By Donna Engle, Photos by: Phil Grout

Together, black and white Carroll Countians will honor Martin Luther King Jr. in January. Together, they will teach another generation about the civil rights leader whose non-violent protests generated a revolution against segregation.

Whites and blacks together make a symbolic statement in a county where a black child in Johnsville in the 1950s would be told, “No, you can’t play out in the yard this evening. The Klan rides tonight.” And where a black child in Winfield watched school buses carrying white children go by as she walked two miles to catch a bus to Westminster, to all-black Robert Moton High School.

Three local events celebrate King’s birthday: Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Breakfast sponsored by Carroll County NAACP Branch 7014; “A Day On, Not A Day Off,” a program for students co-sponsored by Carroll County Public Schools (CCPS), McDaniel College, Carroll Community College, the Ira and Mary Zepp Center for Nonviolence and Peace Education, and the Carroll NAACP branch; the South-East Historical and Educational Civil Rights Tour, sponsored by the Zepp Center.

The annual King breakfasts were started in 1973 by the Former Students and Friends of Robert Moton. When the organization discontinued the breakfasts in 2003, the Carroll County NAACP branch stepped in.

“We wanted to have some representation of the importance of Dr. King in the county, to honor him,” said Jean Lewis, NAACP branch president. Youths traditionally have a role in the breakfasts. They might share letters to King or discuss the lives of black heroes.

The “A Day On” program on the federal holiday began five years ago when the school system received a grant for activities related to King.

“The grant ended, but we continued because we felt students needed to know what Dr. King stood for, not just to stay home and watch TV,” said Patricia Levroney, CCPS supervisor of equity and community outreach. The program is open to students in grades 3 through 12. Those in grades 6 through 12 receive service learning credits for the day. Programs have included celebrations of King’s life by guest speakers and in song.

This year, “A Day On” features a re-enactment of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom that brought hundreds of thousands of people to the nation’s capital in 1963. Students will meet at McDaniel College, then march to Union Street United Methodist Church, an historically black church, carrying peace signs. They will tour the church and then march to the Shepherd’s Staff, a Westminster outreach and support center, to donate items for people in need. The day will include an African dance performance at the Carroll County Arts Center by Sankofa Dance Theater of Baltimore.

“We are looking for historical moments where the children can understand this is where America comes from,” Levroney said. Issues the African-American community faces today are the same as they were in 1963, she said: jobs, equality, services, voting rights.

The civil rights tour retraces King’s non-violence campaigns, stopping at battlegrounds of the civil rights movement, from Georgia across Alabama and Mississippi.

“It is a celebration of the progress in civil rights and the work we still have to do,” said Pamela Zappardino, co-director of the Zepp Center with her husband, Charles Collyer. The tour is guided by Bernard Lafayette, a leader of the 1960s civil rights movement.

“A lot of people tell us the tour changes them,” Zappardino said.

Carroll residents attended the March on Washington for individual reasons, but shared a viewpoint: segregation rankled.

“When I think about it now, it brings tears to my eyes,” said Sally Dotson Greene, of Winfield. In 1963, she was a 28-year-old, afraid to go to the march, but angry. She mustered her courage to go on the trip to Washington.

“Within myself, I had a lot of anger,” Greene said. As a child, she was angry about not being allowed to attend neighborhood schools because of her race. As an adult, she watched whites receive promotions that she did not get. The day brought her a sense of peace, but she believes true equality has not been achieved.

“I really thought things would be better than they are. Now we don’t have signs saying ÔWhites Only’ but there are invisible signs,” Greene said.

The civil rights activism of John Lewis, 77, of Sykesville, grew out of a child’s sense that it was unfair he could not play outside because men in white sheets might ride by, unfair to see disparity in facilities and programs when Moton students visited white schools, unconscionable to hear about a relative killed by a white man who was never charged.

As an adult, Lewis began fighting discrimination locally, persuading the owner of Frock’s Sunnybrook Farm to open the swimming pool to blacks, persuading restaurants to serve blacks. He lobbied in Annapolis for the public accommodations law, demonstrated at the whites-only Carroll Theater, filed complaints against restaurants that refused to serve blacks, and served on the Carroll County Human Relations Task Force.

When Lewis told his family he was going to the March on Washington in 1963, “The first words out of my mother’s mouth were, ÔYou won’t come back. You’ll get shot,’” he recalled. He was scared, but fear evaporated amid the sheer size of the crowd, King’s words and the marchers’ peaceful behavior.

Charles Harrison of Sykesville grew up in Turners Station, an all-black community in Baltimore. For him, the faces of discrimination included singing in high school choir competitions that black schools never won and visiting other schools that had programs and facilities his school lacked.

In 1963, Harrison was 16, a member of a youth corps sponsored by the local NAACP branch. The group booked a bus to the March on Washington. Harrison’s parents tried to dissuade him, but gave permission because his older brother was also going.

Harrison returned from the march with the sense, “that I am on the same level with everyone else,” he said.