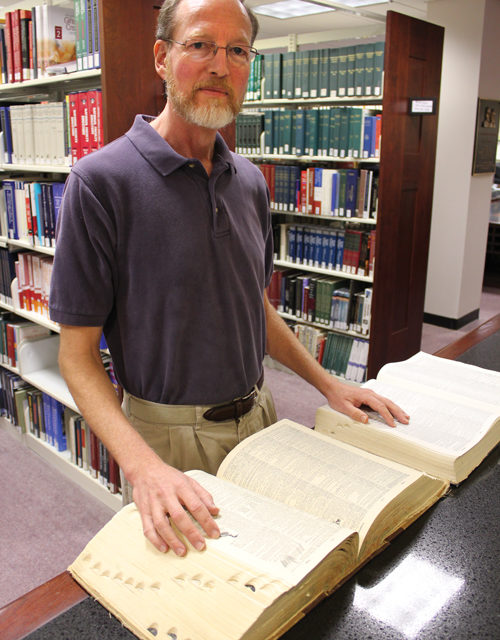

Orin Hargraves works with words, but he also loves to travel, is an amateur birdwatcher and gardener.

Written By Lisa Breslin

How does one become a lexicographer, i.e., a compiler of dictionaries.

Twenty years ago, Westminster resident Orin Hargraves responded to an advertisement in a London newspaper, The Guardian. It was not such a glorious ad; in fact, all he remembers is that the notice sought a native speaker of American English who had experience teaching English as a foreign language.

Hargraves was in fact teaching English as a foreign language in London at the time, so he had the confidence to take a few tests and tackle a few interviews.

“And from there,” said Hargraves, “I launched into my current, long-time career as a lexicographer.”

Lexicographers are few. In fact, Hargraves estimates that he is one of 100 in the U.S.. After all, “dictionary compiler” is one career for which there is no specific degree. A liberal arts education offers great context for a job that calls for sifting through databases and drawing out instances of usage: hundreds, sometimes thousands of examples of a word until the compiler can write an accurate definition.

“I determine the parts of speech and I decide in how many senses the word needs to be defined and how many examples need to be incorporated,” said Hargraves.

“Each project has a specific need,” he said. “And that need – that audience – dictates how many senses to split the word into, how many examples to offer, how many illustrations, etc.”

Lexicographers get paid by the project, per definition or per 100 entries; and although the framework for pay differs, pay translates to approximately $40 dollars an hour.

A University of Chicago graduate who majored in philosophy, languages and literature, Hargraves first broke into the publishing field through the back door.

“After college I was a typesetter,” he said. “Then I worked for a manufacturer publishing software, and then I went into printing. So when I launched into lexicography, I had some indirect experience.”

During his early years, Hargraves said, couriers would arrive at his desk about every three days with a package of pages printed by various publishers. He would note the edits and the additions on those hard copies. Annotations about cross-referencing were done on index cards and forwarded via the courier to other lexicographers.

“For 500 years, people wrote dictionaries without electronic databases,” Hargraves said. “I did, too, for about three years, but I can’t imagine that working now.”

One person rarely authors dictionaries. In fact, Hargraves estimated that between 30 and 50 people collaborate on each book.

A typical project, which calls for finding new definitions, might take six months. To write a dictionary from scratch, which Hargraves has worked on, takes about 30 to 40 people three years to complete.

Hargraves has worked for Scholastic, Oxford University Press, Cambridge Press, HarperCollins and Merriam-Webster.

His recent projects include work on an idioms dictionary and a children’s dictionary. The idioms dictionary enabled him to have fun with the term “nitty-gritty” for a while.

“Most people think that the origin is linked to the phrase Ôget down to the nitty-gritty,’” said Hargraves. “But people also use it as an adjective: nitty-gritty details, for example. It doesn’t mean one thing. The phrase became popular because of its rhymes.”

When Hargraves defines words for children, he has to mull over various possibilities until he can home in on a definition that children can understand; one that piques their curiosity and leaves them wanting more; one that doesn’t overwhelm them or push them away.

Ruminating about words is one of the many things that Hargraves loves about his work. Another perk that he appreciates is that as long as there is Internet access, he can work from anywhere. And Hargraves loves to travel.

He also describes himself as an amateur birdwatcher, a gardener (especially vegetables), and a (bad) piano player. He finds solace at the International Meditation Center on Rose Drive in Westminster, where he often volunteers.

This summer Hargraves will teach a lexicography course at the University of Colorado. The Linguistic Institute of the Linguistic Society of America sponsors the course.

“This is a field where you get to work with really intelligent people who love words,” he said. “Even though I have been writing for a long time, I still love it when the dictionary is complete and my free copy arrives at home. I flip to the page of authors to confirm that my name is spelled correctly and then it’s fun to look through the book to see if anything of what I wrote survived the editing process.”

In addition to dictionaries, Hargraves’ other books include The Big Book of Spelling Tests, Slang Rules, Mighty Fine Words and Smashing Expressions and a series of travel books including Culture Shock: Morocco and Culture Shock: London.

WORD GAME

Orin Hargraves will judge the first annual Scrabble Madness contest.

On Saturday, February 19, from 1 p.m. until 5 p.m. the McDaniel College English Department, the Literacy Council of Carroll County, and the Westminster Rotary Club will host “Scrabble Madness,” a charity Scrabble contest in the McDaniel College Forum.

Teams will consist of one to three people, and the team members must at least be in the sixth grade. The deadline for registration is February 15, but registration will close when 64 teams have entered. The Team Entrance Fee will be $100. The proceeds will benefit the Literacy Council and the Westminster Rotary Club’s community projects.

Registration forms are available at Carroll County Public Library branches, the Literacy Council (Carroll Nonprofit Center; 255 Clifton Blvd, Suite 314;Westminster) and the Carroll Arts Center (91 W. Main Street in Westminster). Forms are also available upon request. Snow date for the contest is Saturday, February 26. Information: mbendels@mcdaniel.edu