by Lisa Gregory

Never Forget

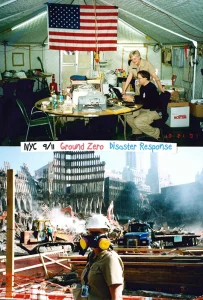

Taneytown Resident Reflects on Work as a Clinical Psychologist at Ground Zero

Each year, as September approaches, Carol Coley readies herself to face her emotional demons once again.

“I am traumatized almost 25 years later,” says the Taneytown resident.

On Sept. 11, 2001, Coley was on an airplane heading to Boston from Baltimore/Washington International (BWI) Thurgood Marshall Airport for a conference. Looking out the plane window, she saw that the North Tower of the World Trade Center in Lower Manhattan was in flames. Then, moments later, she witnessed a plane hit the South Tower. “It was just total silence,” she recalls of the environment inside the plane’s cabin.

Coley, then a clinical psychologist with the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, would not just witness the horrific tragedy of that day but soon face the biggest challenge of her professional career. She would be sent to New York City to coordinate and oversee mental health crisis services in the days ahead.

But first, like other Americans, she had to grapple with the shock of what had just occurred. After her plane landed in Boston that day, “Everyone was just piling into taxis, and they didn’t care where they were going,” she says. “They were just getting away from the airport.”

She went to her hotel. Shortly after arriving, she learned her hotel was the same place where two of the terrorist hijackers had stayed before they boarded planes that morning. As Coley settled in, “All these bells start going off, and we are all evacuated,” she says.

While waiting to return to her room, Coley saw a colleague frantically trying to contact her daughter and son-in-law, who lived very close to the World Trade Center. “I just went over to her, and we held each other, sitting on the floor, rocking back and forth,” she says. “I just took care of her until I could get her calmed down a bit.” Her friend later discovered that her daughter and son-in-law were safe in New Jersey.

As a captain in the Commissioned Corps of the U.S. Public Health Service, or USPHS Commissioned Corps, one of the nation’s uniformed services, Coley served those affected by the aftermath of disasters. As such, she witnessed the emotional fallout from wildfires, hurricanes and school shootings — none compared to her experience at Ground Zero.

“It was like Hiroshima,” she says. “Everything was gray. There was no grass. There were no leaves. There were no birds. There were no bugs. You would be covered in this light dust still falling from the sky. It made little pinpricks in your clothes. The acid was eating your clothes.”

Coley served at Ground Zero for several weeks in October 2001 to monitor those who might be experiencing distress as they searched for bodies and often came up with just body parts. “Maybe a finger,” she says, a finger that had once belonged to a whole person who lived and no doubt loved and had made plans for the next day. Coley remembers seeing remains gently taken and placed on a golf cart-like vehicle, covered with an American flag and escorted off the site by several workers in a silent and respectful march. “There was a whole honoring system meant for the whole body,” she says. “These were just little body parts. But they would do it the same way. Most people were never identified,” she adds.

Observing these workers, which included firefighters, police officers and construction workers, from the sidelines, Coley and her colleagues “were looking for that 1,000-yard stare,” she says of the blank, emotionless expression people sometimes experience with acute stress or dissociation. “Or, if they might be isolating themselves, or maybe someone had found remains and just fell apart.”

It was no easy task for those called to monitor signs of mental distress. Many, including Coley, were struggling with emotional fatigue. But like those searching through the debris, Coley and her colleagues had a job to do and were committed to doing it. “You just have to go into clinical or disaster mode,” she says. Despite it all, she says she was “proud to be there and helping where I could.”

Coley, originally from Missouri, was drawn to the well-being of others early on in her life. At age 10, Coley, an only child, lost her mother to cancer. “That’s when my childhood ended,” she says. Her feeling of loss and her attempt to understand it would inspire her career choice in many ways. “I was interested in the puzzle of people and trying to figure out who they were and how they were put together and what parts of them I could help,” she says.

Coley received her bachelor’s degree from the University of Missouri and her master’s degree from Central Missouri State University. She began her clinical career as the psychological services director at a youth center for troubled adolescent girls exhibiting mental health disorders.

She left Missouri in 1986, moving to the Washington, D.C., area and became the clinical administrator with the Cuban Refugee Mental Health Program. From there, she began her USPHS Commissioned Corps career with the National Institute of Mental Health in 1990. She went on to work with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

As a seasoned psychologist, Coley was aware that she needed to find her own comfort and respite as she worked at Ground Zero. She and so many others found refuge in a small church that, despite the destruction around it, was still standing. Musicians from the New York Philharmonic were brought in to play, and one could find a pew and have a few moments of silent reflection.

“I would go twice a day,” says Coley. “I would close my eyes and listen to the music.” Coley remembers the day a harpist played and the comfort the music brought her weary soul amid so much destruction and loss.

An animal lover all her life, Coley, now a dedicated volunteer with the Humane Society of Carroll County, watched as veterinarian volunteers treated the search and rescue dogs who injured their paws from climbing through the debris at Ground Zero. However, there were other dogs there as well — comfort dogs. “People would just show up with them from all over the country,” she says. “I ran up every time I could to pet them.”

She found comfort in other unexpected ways as well. She remembers passing by a card of well wishes taped to the wall of a mess tent where she went to eat. “It was from the nursing home just two blocks from where I worked back in Rockville, Maryland,” she says. “I took a picture of it, and when I got home, I sent the picture to the rest home and told them how much it had meant to me,” she says.

She needed these random moments of kindness and care. Her workdays ran 10 to 14 hours. Going on “autopilot,” she endured the emotionally exhausting days. However, once alone in her hotel room, it all came crashing down on her.

“The worst was when my cousin from Kansas called and wanted to talk and see how I was doing,” she says. “That familiar voice just broke right through, and I started crying. I asked her not to call me again. I couldn’t talk about it.”

On the last day she was in New York City, she drove past a line of people in the traffic median, whom Coley had seen day after day as they stood there offering support and thanks. “It always gave me goosebumps,” she says.

This time, she stopped. “I got out of the van, and I went up to the line and hugged every one of them,” she says.

Coley was glad to return home, but being at home would be challenging. “I stepped off the train and fell, sobbing, into the arms of friends waiting for me,” she says.

After six months at home, she sought therapy for herself.

“I remember standing on my deck and thinking, ‘I am not handling this very well,’” she says. Coley was easily startled and had begun to isolate herself. And, of course, she was going through all these emotions as she continued her job. The world and its tragedies did not stop after 9/11. The first crisis she had to work on after returning from New York City was a school shooting.

She met her job responsibilities and did them well. “It was hard,” says Coley, who retired in 2010 and has lived in Taneytown since 2005. Since retirement, in addition to volunteering at the Humane Society of Carroll County, she has also served such organizations as the CARE Healing Center (formerly the Rape Crisis Intervention Service of Carroll County). “I wanted to continue being there for others,” she says.

Therapy helped her process and better cope with those days spent at Ground Zero. But 23 years later, she admits she still struggles. “It changes who you are,” she says. Each year, on Sept. 11, she tries to shut out the world. “No television, no radio, no papers,” she says. Instead, she surrounds herself with those she loves, including her partner Sam, her friends, her family and her pets.

Yet, no matter how hard she tries, she still remembers. She will never forget.