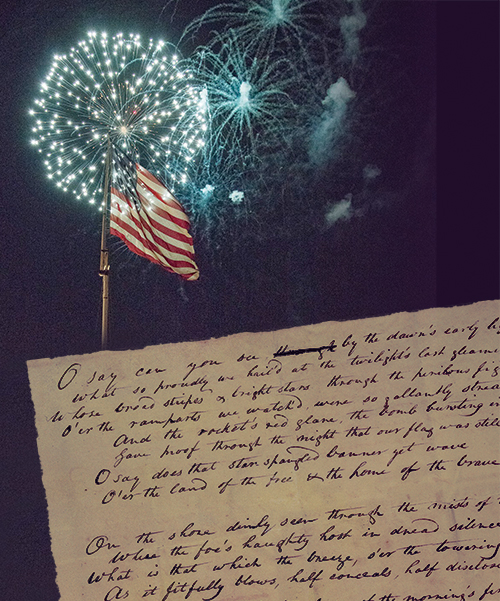

Fireworks light up the skies at Fort McHenry with the Star-Spangled Banner. Below is a copy of the written words to the The Star-Spangled Banner. Photos courtesy of the Maryland Historical Society, photographer Tim Ervin.

Written By: Jeffrey Roth

As the nation pauses to celebrate the 200th anniversary of the Battle of Baltimore and the penning of “The Star-Spangled-Banner”, the life of Francis Scott Key is drawing national attention.

Catherine Baty, author and curator of the Historical Society of Carroll County, noted that Francis Scott Key was born Aug. 1, 1779, on the 3,000-acre plantation Terra Rubra (Latin for red earth), now a 149-acre farm located along Pipe Creek, just outside Taneytown. The son of Ann Phoebe Penn Dagworthy (Charlton) and Captain John Ross Key, he was born in what was then Frederick County.

“Eventually, he inherited the farm from his father,” said Baty. “Although he owned the farm throughout his life, he spent most of his time living elsewhere. He had both a home and law practice in the city of Frederick.”

The current Federal-style house on the Keysville-Bruceville Road was built in the 1850s after the original Key residence was damaged in a storm and had to be replaced, Baty said.

Key was educated at home until he turned 10, at which time he attended a grammar school in Annapolis. Eventually, he enrolled in and graduated from Annapolis’ St. Mary’s College.

“Key’s father, (who had served as a captain in the Continental Army), was a farmer, an attorney, and later became involved in politics, eventually serving as a judge in Frederick,” said Baty. “Francis Scott Key married Mary “Polly” Taylor Lloyd and they had 11 children.”

It is not clear where Key lived or worked following his graduation from college in November 1800, said Chris Haugh, scenic byway and special programs manager for the Tourism Council of Frederick County.

Some historians speculate that Key may have lived with his uncle, Philip Barton, who served as mayor of Annapolis. Others suggest he may have returned home to Terra Rubra, while working under another lawyer.

“I think he was in Frederick in 1801, since he married in 1802,” said Haugh. “Nobody has ever been able to discover the location of his residence.”

Key’s wife was the daughter of the second- wealthiest family in Maryland and lived in Annapolis, Haugh said. Polly Lloyd was active in the capital’s social scene, and was “not excited to live in Frederick Town, where there was no social scene.”

In September of 1803, their first child had been born, and by then it was certain that they lived in Frederick. By 1805, Key had opened a legal practice in Georgetown, near the nation’s new capital.

While working as an attorney in Georgetown, the hand of fate would guide Key to a truce ship in Baltimore Harbor on Sept. 13-14, 1814, where he witnessed the British naval bombardment of Fort McHenry during the Battle of Baltimore, said Ranger Paul Plamann, an interpretative historian at Fort McHenry. Plamann portrays Dr. William Beanes, a colleague of Key, from the Upper Marlboro region of the Chesapeake Bay.

“The good doctor is the one who gets Key involved in the story of the fort and the bombardment,” Plamann said. “Key, Dr. Beanes, along with Col. John Skinner, became eyewitnesses to the 25-hour attack.”

When British troops captured Washington, D.C., Dr. Beanes was taken prisoner, Plamann said. Friends of Dr. Beanes contacted Key and asked for his assistance in negotiating with the British for the doctor’s release. The negotiations were a success, but because all three men knew of the British battle plans, they were held on the truce ship until the bombardment ended.

Plamann said Dr. Beanes’ arrest followed an earlier incident in which British forces commandeered the doctor’s house. Later, Dr. Beanes and other community leaders captured and arrested several deserters and stragglers who were identified as British soldiers. Dr. Beanes “wanted to teach them a lesson and had them jailed,” Plamann said.

“When word got back to British commanders that their men had been jailed, needless to say, they weren’t very happy,” Plamann said. “The British sent soldiers to release the jailed men. Dr. Beanes was one of the people identified as being responsible for the incident. He was hauled off during the middle of the night and eventually put aboard a British ship.”

Civilian non-combatants, by “gentlemen’s agreement,” were not to be treated as military prisoners of war, Plamann said. As a result of the incident, Col. Skinner, who had acted as an agent in previous prisoner exchanges, along with Key, agreed to meet the British commanders, Plamann said.

First, Dr. Beanes, was taken aboard the HMS Tonnant. Key and Skinner negotiated Dr. Beanes’ release. Eventually, the three men were transferred to an unidentified American truce ship which was anchored about eight miles away in the Patapsco River.

At 6 a.m., Sept. 13, 1814, a fleet of about 19 ships fired upon the fortress, which was manned by about 1,000 American soldiers commanded by Maj. George Armistead. The attack included the firing of 1,500 to 1,800 Congreve rockets from the HMS Erebus, along with a barrage of mortar shells fired by gunships.

“The British Congreve rocket could be used on both land and sea,” Plamann said. “Sir William Congreve, in 1804, developed the rocket system to adapt it to military use. The use of the rockets at the Battle of Bladensburg (Prince George’s County), Aug. 24, 1814, was instrumental in causing some of the American militia troops to flee the field of battle.”

Although it was not very accurate, the black powder-fueled cylindrical rocket had a range of up to two miles. The missile was attached to a wooden guide pole and was variously equipped with an explosive warhead, shrapnel or incendiary device, Plamann said. Congreve rockets were the 1814 British version of a shock and awe attack, and served primarily as a psychological weapon.

Early in the morning of Sept. 14, 1814, the British bombardment stopped. Key, an amateur poet, attempted to determine whether the 30-by-42-foot U.S. flag still flew or had been lowered, indicating that the American forces had surrendered, Plamann said.

By coincidence, at about the same time, the garrison was ordered to raise the flag. Major Armistead had requested a “flag so large that the British will have no difficulty in seeing it from a distance.” That flag, which now is part of an exhibit at the Smithsonian, was made in 1813 by a Baltimore flag-maker, Mary Pickersgill, and her assistants for a $405.90 commission.

There are two historical ironies involving the Fort McHenry flag and The Star-Spangled-Banner. The first: Pickersgill used a combination of cotton and dyed English wool bunting to make the flag with its 15 stripes and 15 stars. The second: the lyrics of the poem that Key wrote, entitled “The Defence of Fort M’Henry,” was wedded to a popular British melody, “Anacreon in Heaven.”

On July 4, 2013, more than 200 volunteers, along with 1,000 honorary stitchers, spent six weeks hand-sewing about 150,000 stitches to recreate Pickersgill’s 1813 flag. Burt Kummerow, president and CEO of the Maryland Historical Society, which sponsored the $12,000 project, said the volunteer leaders visited the Smithsonian to view the original flag, and used the Smithsonian analysis of its fabric to make a historically authentic replica.

A Red Lion, Pa., textile mill, Family Heirloom Weavers, which specializes in recreating original historic fabrics, provided the material for the flag project, Kummerow said. Dyeing of the flag was done by two companies, Jagger Brothers and Saco River Dyehouse, both located in Maine.

“We started with ‘The Star-Spangled-Banner’ manuscript, which is the very first copy written by Francis Scott Key,” Kummerow said. “My whole point of view is that people often consider historical societies to be irrelevant these days. We wanted to do something that really touches a nerve, as does ‘The Star-Spangled-Banner’ manuscript, which is currently on loan at Smithsonian and is in the chamber with The Star-Spangled-Banner flag – the very first time the two have been exhibited together.”

Ruth Ann Robinson, the curator of Old Line Museum, a small regional facility in Delta, Pa., spent more than 50 hours working on the flag replica. She learned of the project while touring the mill of the Family Heirloom Weavers, and decided to become involved.

“I was one of over 200 volunteers who stitched the flag,” Robinson said. “There were also approximately 1,000 commemorative stitchers, such as the mayor of Baltimore, politicians, other public figures and random visitors who stopped by to put in one stitch.”

As with all historic figures, fact merges with legend in creating the public perception of Francis Scott Key, said Marc Leepson, a historian, journalist and author of the first new biography of Key in more than 75 years. On June 24, his book, What So Proudly We Hailed: Francis Scott Key, A Life, debuted to the public. Leepson’s other works include Desperate Engagement, which details the Battle of the Monocacy; Lafayette: Lessons in Leadership from the Idealist General; Flag: An American Biography; and Saving Monticello: The Levy Family’s Epic Quest to Rescue the House that Jefferson Built.

“Up until relatively recently, historians believed Key was writing a poem that night because he was an amateur poet,” Leepson said. “He was not musical and he had never written a song in his life and may have been tone deaf. Now opinion has changed. Back in that time period it was common for people to take lyrics and put them to a well-known tune. This tune was very well known.”

Key spoke publicly about writing “The Star-Spangled-Banner” only once, 20 years later, Leepson said. At the time, “The Defence of Fort M’Henry” was one of many patriotic tunes. It did not become the national anthem until 1931.

Of all of Key’s descendants, only one would reach prominence for his written works, Leepson said. That writer, also born in Maryland, was The Great Gatsby author, F. Scott Fitzgerald.

There are numerous events scheduled to commemorate the 200th anniversary of the Battle of Baltimore and “The Star-Spangled-Banner,” culminating with a September 13 concert at Fort McHenry and at the Baltimore harbor. Tall ships and U.S. Navy ships will arrive September 10 and will be open to tours on September 11. Other activities are being held in connection with the celebration.