2016 Olympian Katie Zaferes, formerly Hursey, wasn’t always a runner, nor was she a biker, a swimmer, or a triathlete. The Hampstead native began picking up the pieces to her professional triathlon career long before she realized it was even a dream.

At North Carroll High School, the 2007 alum played soccer for her first two years and lacrosse her freshman year. After her first year of track, her coach encouraged her try cross country. Zaferes vividly remembers talking to her soccer coach on picture day — still wearing her uniform — when she told her coach she would be running cross country instead.

When she swapped cleats for spikes, Zaferes had no idea that decision would lead to two Girls Cross Country Runner of the Year awards, four Carroll County Times Athlete of the Year Awards and three state championships in track and field.

She had no idea she would run at Syracuse University where she graduated as the school record holder in the 3000-meter steeplechase and the indoor 5000-meter run.

She had no idea that in 2013, she would be named 2013 USA Triathlon Elite Rookie of the Year, or that in 2015 she would podium six out of the eight races in the International Triathlete Union (ITU) World Triathlon Series, or that she would win her first World Triathlon race in Hamburg Germany.

She had no idea that on May 24, she would secure her spot at the Olympics and that on August 20 she would finish 18 as the second American.

As a member of the North Carroll High School cross country team, Zaferes won two Girls Cross Country Runner of the Year awards.

“I just find it so crazy how all these really tough decisions at the time have led me to the awesome life I get to live now and ultimately to becoming a triathlete,” Zaferes said. “I never really liked running when I started — I just did it because it was something I was good at. I learned to love it though, through running at North Carroll and then at Syracuse University.

Not just a runner, but also a fish — Zaferes began swimming competitively with the North Carroll Sea Lions and Westminster YMCA when she was eight. While competing in high school sports, Zaferes juggled year-round swim practices and meets, oftentimes doing back to back practices, said her swim coach Mike Kremer.

Although Zaferes and her parents never foresaw Katie as a triathlete, Kremer realized Zaferes’ incredible running and swimming times were two of the three the puzzle pieces to create a triathlete — all she needed was a bike, Kremer had said.

In 2007, Zaferes ran her first triathlon, the Father’s Day Tri-to-Win South Carroll Triathlon, with her dad.

At the end the race, Zaferes was thinking about the pride she had for her dad, who had learned to swim several weeks beforehand — becoming a professional triathlete and competing in the Olympics weren’t even glimmers of a dream for Zaferes.

“I had no thoughts of becoming an actual triathlete at that point,” Zaferes said. “It was just something I was doing with my dad for fun. It’s funny now to look at pictures and how I have grown as a triathlete since then. Everyone has to start somewhere.”

It wasn’t until her senior year at Syracuse that she began to run triathlons seriously. After a recruiter for USA Triathlon Collegiate Recruitment Program contacted Zaferes, she began training at the Olympic Training Center in Colorado Springs in 2013.

Behind Zaferes is a group of people willing her to succeed — family, friends, coaches and others in Carroll County.

“Our community is just so close knit and supportive,” Zaferes said. …“It’s also the place that shaped who I am today, and in a lot of ways led me to triathlon in one way or another. So it’s just really amazing to get to show my Hampstead and Carroll County pride on a world level.”

Zaferes keeps people informed with her blog page where she posts updates of training and racing that she writes all in rhyme.

People have contacted her, Zaferes said, simply to tell her that they are proud and cheering her on.

“…I’ve been so touched by the amount of people that are supporting me in this endeavor,” Zaferes said several weeks prior to her Olympic race. “Before every race I’m just filled with gratitude almost to the point of happy tears that I have so many amazing people behind me. My family and friends also just make my heart full in knowing that they are proud of me no matter what.”

Before her Olympic race, both of Zaferes’ parents said just that — highlighting her humility, not her medals.

“We’re always very proud of Katie’s accomplishments but we’re always most proud of who she is and how she treats others. The pride is in who she is, not in what she does,” said Mary Lynn Hursey.

Zaferes’ high school cross country coach, Foyle, said that Zaferes came to her incredibly disciplined, motivated and willing to seek new challenges. What sticks with Foyle the most however, is how Zaferes would finish a race, stand at the finish line and cheer for not just her teammates but everyone on the course.

“I was more proud of her as a person than as a runner. As a human being she excelled at making others feel like they were number one,” Foyle said. “They might have been the last finisher, but she made them feel they were the best. It really touched people to have the best runner patting them on the back.”

Kremer said that it’s been great to see Katie not only succeed but also become a role model.

“I know she will do a lot of good with [her success] for the community around her. …[The Olympics] gives her that opportunity to be that voice and role model for our youth,” Kremer said. “I think Katie would take that opportunity and do a lot of positive things with it. …We need more like her.”

Always a Wrestler; Now an Olympian

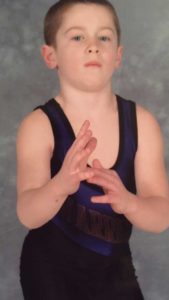

Kyle Snyder of Woodbine is as uncompromising on the wrestling mat as he is with his ambition. His most recent accomplishment, becoming the youngest American wrestler to win gold at the Olympics, was prefaced by a wrestling career that began in Carroll County when he was five years old.

At first wrestling was a way for Snyder to expend his playful energy, said Snyder’s dad, Steve Snyder, but his love for the sport stuck.

Snyder wrestled for three years at Our Lady of Good Council high school as the three-time state champion with a 179-0 record. His senior year, he transferred to a school in Colorado Springs to train at the Olympic training center, and that summer he won the Junior World Championship.

“I wanted to be the best wrestler I could possibly be and the OTC supplied me with the necessary materials for me to do that,” Snyder said.

“Kyle had no one else to train with here in Maryland,” Steve Snyder said. “He had pretty much exhausted partners. Even the coaches couldn’t wrestle with him anymore.”

South Carroll wrestling coach, Brian Hamper, began coaching Snyder through the Warhawks Wrestling Club when he was in middle school. Even from an early age his peers were always trying to keep pace, Hamper said.

As one of several of Snyder’s coaches throughout the years, Hamper said that it was never really a question that Snyder would achieve his Olympic dream because when Snyder steps onto the wrestling mat, he’s there to win.

At the age of five, Kyle Snyder began his wrestling career in Carroll County with current South Carroll wrestling coach Brian Hamper.

When Snyder is in a match, he’s not looking at the score board and wondering how he can maintain his lead—he’s solely concentrated on how to score the next point, Hamper said.

“That’s what makes him so dangerous on the wrestling mat. He breaks people. You see grown men crumble on the wrestling mat. He keeps a pace that not many people can keep up with,” Hamper said. “Six minutes on the wrestling mat with Kyle Snyder seems like an eternity.”

As difficult as it is to keep pace with Snyder on the mat, keeping up with his list of accolades is just as challenging—All American Honors his freshman year at Ohio State, 2015 NCAA wrestling champion, youngest wrestling world champion in the U.S. and a list that just keeps growing.

Of course, not all wrestling matches have ended in glory for Snyder.

His freshman year at Ohio State, he lost in the final match at the 2014 NCAA tournament—yet for his parents, it was still an incredibly proud moment.

Shortly after the match, Kyle was asked to speak in front of a small audience.

“The way he carried himself… It was heart wrenching but I was extremely proud watching him [do] what he did after that,” Steve Snyder said. “It was pretty amazing watching him being able to do that.”

It speaks to Snyder’s character that he was able to rebound from his loss, said his mom, Tricia Snyder.

“When something bad happens, you can capitalize on it and have a good thing come out of it, which is what he’s done,” Tricia Snyder said. “He loves the sport, and I think that’s probably what kept him focused. It was painful to lose and lose in that way, but that’s not all that he wanted to accomplish.”

Snyder has never been one to dwell on victories and defeats—Hamper said that if he knows Snyder at all, then the new Olympian will be proud of his gold medal but already looking for that next challenge. “He’s going to be right back in the room doing the things that make him great again.”

As Kyle moves forward, he leaves behind an example of what it means to be a student-athlete by “living the lifestyle”—getting it done in the classroom, waking up early to train, eating right and living his life in a way to achieve his goals, Hamper said.

Despite his success, he’s remained humble and has never wavered in who he is as person—and it is this, Hamper said, that makes him most proud of Snyder.

When Snyder returns from Ohio State, he coaches wrestlers who are starting out just as he did.

“He’s definitely made a lasting impact. He’s definitely willing to come back and give back to the community,” Hamper said. “He goes above and beyond. Every times he’s back he reaches out and pours out into these kids. He’s a phenomenal coach and a phenomenal role model.”

That impact Snyder is leaving gives young wrestlers a chance to dream too.

“He’s a larger than life person, and knowing that he worked out in the same rooms that they did makes it seem possible for them,” Hamper said. They look at him as if he’s a wrestling super hero… If you live the right way that goal is still achievable.”

Snyder said he likes giving back to the community through wrestling because of the great coaches who helped him.

“Hopefully, I can inspire people to be great at whatever they love to do,” Snyder said. “It doesn’t just have to be a sport. Find something you love and do everything you can to be the best you can be at it.”