by Lisa Moody Breslin and Rebekah Cartwright photography by Phil Grout

Over the past year, events in Ferguson, Baltimore and Charleston have led to an ongoing national dialogue about race. As part of our mission to engender deeper conversations among our readers, Carroll Magazine spoke to several minorities to learn more about what race looks like from their perspective in our community.

We asked questions about living in the county as a minority. We asked about the role of race in their personal pursuits. We wondered if tensions in counties far from here and as close as 45 minutes away mirrored tensions here. Or, for this small group of people, could Carroll County be a better place – one not perfect – but better.

When Javoke and Jennifer Terrell moved to Carroll County from Texas 11 years ago, they searched for a diverse neighborhood rooted in a strong school system.

Baltimore was not an option. They had heard just enough about some of the schools and tensions in some of the neighborhoods to know they didn’t want to call Baltimore home.

Howard County caught their eye, but it was too expensive.

“And then our realtor told us about Carroll County,” said Jennifer. “The school system looked great. The classes offered to our children were similar to classes in private schools.”

Diversity?

“We were a little shocked,” Jennifer said. “When the family went to the mall in Columbia, the children’s earliest comments included ‘Wow, it is so much more diverse here.’”

But according to the couple, Carroll County has always welcomed them and their three sons, Quentin Jones, Chris Parker and nine-year-old Xavier.

Carroll County has traditionally been a rural farming community. The county has seen growth, in residential and business construction, in recent decades, helping to increase diversity in the county. Even with growth and diversity, the U.S. Census reports that in 2014 there were approximately 168,000 residents in Carroll County, 3.5 percent of whom are African American.

“I worked for the president of Carroll Hospital Center [John Sernulka] and that made a difference in a lot of things,” Jennifer said. “Mr. Sernulka, the board members and the hospital family embraced my family and I.”

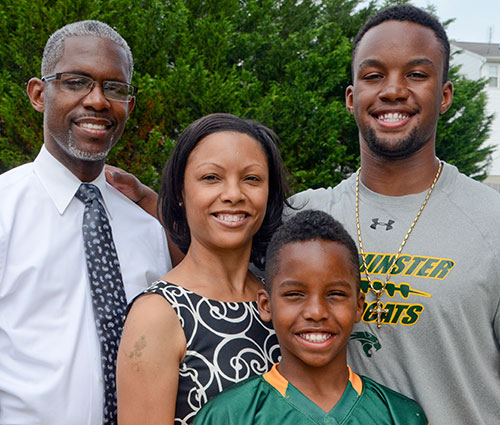

Chris Parker, younger brother, Xavier, 9, along with his mother, Jennifer and stepfather, Javoke Terrell.

“I know I was concerned about my oldest son [Quentin Jones] being the only African American in his class the majority of the time. For instance, when Obama was elected or there was discussion in history class about slavery, he’d come home and say, ‘Everyone looked at me.’”

Whether for a reaction or to start discussion, Jennifer said they looked to, and at, her son to be the voice for all black people.

“But overall, we didn’t have any problems. We kept the children involved in school activities and I stay involved,” Jennifer added.

This level of racial acceptance has been a work in progress in Carroll County, with an incident involving racial graffiti at Westminster High School just 7 years ago, according to a Reuters article.

Some of Carroll’s residents remember living here before there were laws requiring restaurants to serve black citizens, before sports teams were required to allow African American youths to participate, before schools were segregated and before black kids were allowed to swim at the public pool.

John H. Lewis, Jr., born in Sykesville in 1935, has been interviewed at length about his experience growing up African American in Carroll County for the Community Media Center’s Carroll County History Project.

Lewis, who has spent a life time advocating for racial equality, said that his participation in Boy Scouts at the age of 10 or 11 offered him his first understandings of discrimination. He said that in his Boy Scout troop, everyone worked as a unit – race and religion didn’t matter.

“We were taught in Boy Scouts that we were our brother’s keeper. We all had to rely on each other to survive,” Lewis said in the Carroll County History Project video.

It was returning from those adventures that allowed him to see a distinct difference in how people treated him.

“It was as if we were in a different world. It was then that I began to notice this terrible thing called discrimination,” Lewis said. “When we came out of the woods we came back into the realm of reality. But there, in the woods, it was as if we were all one.”

This past spring, the Carroll County Human Relations Commission awarded John and his wife Jean for their tireless efforts in advocating for racial equality in the county and state over the past five decades.

Their efforts have paid off for many families living in Carroll County today, like Jennifer and Javoke Terrell.

But national events, and surely some local ones too, offer a constant reminder that even though African Americans have more rights than they used to, that America has not yet achieved a state of gray. There are clearly still black-white divides.

Racial tension that unfolded in Ferguson, Baltimore and Charleston seemed worlds away from Jennifer’s children, “because they have never lived in an area that fostered or exhibited negative race relations.”

Jennifer said that it’s difficult for her children to relate to the racial intolerance they see on tv.

Jennifer’s son, Chris Parker, has called Westminster home since he was in second grade. He graduated from Westminster High School in June.

“Race is definitely a factor in Carroll County, but I personally have not encountered many race issues,” Chris said. “I know others have been treated differently or things are said, but that didn’t happen to me. It shouldn’t. The pigment of your skin does not matter. You don’t judge people at all, especially if you don’t know them.”

“I have always been active in both school and community and made many friends,” Chris added. “People got to know me for me and everyone was very accepting.”

Deputy Demonte Harvey works in the Domestic Violence office of the Carroll County Sheriff’s Department.

Carroll County Sheriff’s Deputy Demonte Harvey also feels like he has been accepted for the merits of who he is instead of the color of his skin.

There are close to 80 deputies in the Carroll County Sheriff’s Department. Harvey is one of five African American deputies, a number which closely mirrors the 3.5 percent African American population in the county. One might expect that Harvey would face challenges being a minority in a position of authority in a predominately Caucasian community. But according to Harvey, that’s just not the case.

A deputy in the Domestic Violence Unit in Carroll County, Harvey said that race has “absolutely nothing” to do with his job. In fact, according to him, during his three years as a deputy in Carroll County, he has never experienced racism directed towards him.

Harvey started his policing career about 10 years ago in Baltimore. After five years on the job, he moved to Carroll County, where he spent three years on patrol. Several months ago he was moved to the Domestic Violence Unit.

When Harvey first moved to the area, he admits he worried that he might face racial intolerance. But he said that his race has been a non-issue in his police work.

“Everyone is so polite and everyone is so thankful for what we [law enforcement officials] do. It makes us come to work every day because we don’t get that nasty look; instead we get smiles and a thank you for what we do,” he explained.

Even when dealing with criminals, he said no one has ever commented on his race while on the job.

Sheriff Jim DeWees said that the relationship between law enforcement and the citizens they protect has to be one of mutual respect for each other, regardless of race, gender or nationality.

“We certainly have our challenges here in Carroll County,” Sheriff Jim DeWees said. “But respect for our officers is generally not one of them. We have a level of respect for law enforcement that just doesn’t exist elsewhere.”

Aware that racism and discrimination do exist, even if it hasn’t directly impacted them in Carroll County, Chris Parker often advises his little brother, Xavier: “Don’t let what people say affect you. They may want you to retaliate or put you off track to hurt you and bring you down. Don’t let them. Keep moving toward your goals. Never quit.”

To help him grasp a concept as vast as racial tension Chris alludes to playground dynamics: “Racial tension is like being on a playground for the very first time and the kids will not play with you because you are not from their area and you look different. That’s how one race can exhibit ignorance towards another because of unfamiliarity and the lack of knowledge.”

Like son, like father.

Chris’ advice to his brother echoes the words of his own father, Javoke, who grew up in the inner city of Houston, Texas. Javoke said that most of his male elementary school friends are now dead, most killed because of drug activity.

“That is not the route I opted to go. My parents didn’t finish high school, but they involved me in everything. I decided to be around individuals who were motivated, around people who accomplished things. I put my eyes on them and knew I wanted to get as far as they did and go further,” Javoke said.

A funeral director who has been with families who had to bury their children, Javoke is convinced that the tragedies in Baltimore, Ferguson and other cities in the nation reflect a great divide within the African American community.

“We’ve gone from the generations of families who took pride in going the extra mile in the work force, who valued and even pushed education to a generation that grows more and more disconnected,” he explained.

If this message were shared constantly in places like Baltimore and Ferguson, Javoke, Jennifer, Chris and his siblings are certain those cities’ recent history would have had a different outcome.

“My mother insisted from a young age that my brothers and I hug each other and tell each other we love one another,” Chris said. “She taught us – “I am my brother’s keeper.’”

For more information about the Carroll County History Project and to watch John H. Lewis, Jr.’s entire video interview, visit www.carrollhistory.org. Associate Editor Kym Byrnes contributed to this article.