by Kym Byrnes, photography by Nikola Tzenov

Carroll County Rallies Against the Maryland Piedmont Reliability Project

Carroll County is no stranger to spirited debate. From heated school board meetings to contentious development proposals, residents here have long spoken out about ideas shaping our community’s future. One issue, however, has sparked a rare and powerful unity: the Maryland Piedmont Reliability Project (MPRP).

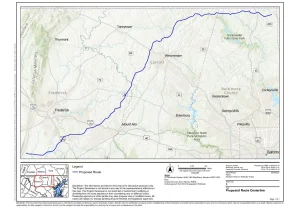

This ambitious plan seeks to construct a 70-mile, 500-kilovolt transmission line stretching across several counties, including Carroll County. Its stated goal is to bolster the state’s energy infrastructure, ensuring reliable electricity as demand rises. For Carroll County residents, businesses, and elected officials, however, these transmission lines are seen not as a solution but as a threat to the rural character, agricultural land and property values defining this community.

Yet this fight raises a broader, more uncomfortable truth: Maryland is in the midst of an energy crossroads. The state’s commitment to closing coal plants and embracing renewable energy sources has created a growing need for new infrastructure to support the transition. Carroll County’s resistance to the MPRP reflects a common dilemma — one that communities across the nation are grappling with. If not this project, then what?

What Is The Maryland Piedmont Reliability Project (MPRP)?

The MPRP’s proposed 70-mile high-voltage electricity transmission line would run through Baltimore, Carroll and Frederick counties. In 2022, PJM Interconnection identified the need to increase the amount of available electricity to the state and diversify the grid geographically. PJM, a Regional Transmission Organization (RTO), coordinates the movement of wholesale electricity in all or parts of 13 states.

William J. Smith, PSEG’s strategic communications manager, explained in an email, “The MPRP is critically needed to prevent widespread and serious thermal overloads on the existing system… If these conditions are left unaddressed, millions of electric customers across multiple states, including Maryland, will be at significant risk for uncontrolled cascading outages or, at worst, blackout conditions as early as 2027 and 2028.”

Despite its ambitious goals, the project has sparked fierce backlash from Carroll County residents, businesses and elected officials. Critics argue that the benefits of the MPRP may not even stay in Maryland. Opponents also point to the social and environmental costs. The transmission lines, supported by towers up to 135 feet tall, would cut through farmland, residential areas and environmentally sensitive lands. For farmers, this means the loss of valuable acreage; for homeowners, it raises concerns about property values and aesthetics. Local environmental groups have also cited the impact on wildlife habitats and fragile ecosystems.

MPRP hints at Maryland’s increasingly dire energy situation for many citizens. The state imports 40% of its electricity from out-of-state sources, and its decision to shut down coal-fired power plants has placed even more pressure on its aging grid. As Maryland Senate President Bill Ferguson (D-District 46) explained in a recent interview on the podcast “Midday,” the state is at a critical juncture.

“When we look at what’s happening with electrification, with data centers and with the challenges ahead for offshore wind energy… the lack of supply tied to increased demand for energy is going to have significant impacts on the price of energy in Maryland if we do nothing,” he says.

PSEG has held a series of public meetings, but many have felt that the meetings were just a formality with few answers and insights offered. Following some initial public meetings, citizens came together to create Stop MPRP, a grassroots, nonpartisan organization urgently working to stop the project. Many feel the project’s public rollout was mishandled, with citizens and elected officials criticizing the company’s lack of transparency and failure to mitigate community impacts.

The project is currently in the early stages of regulatory review. The proposed transmission line cannot move forward unless the Maryland Public Service Commission issues a Certificate of Public Convenience and Necessity (CPCN) to PSEG. In December 2024, PSEG filed an application for that certificate. It could take months or a year or more for the Public Service Commission to make its decision.

Today, the Maryland Piedmont Reliability Project remains a proposal, but its presence has sent shockwaves through Carroll County and is already impacting its citizens.

The Terrifying Reality for Landowners

Beth Gassman lives on a 75-acre farm between Westminster and Taneytown with her husband, five children and her mom. Her children are the fifth generation to live on the land.

“We’re the type of people who hold on to the farm and pass it down from one generation to the next,” Gassman says on the verge of tears. “My mom is 83 years old, and she was born on the farm, married here and has lived on the farm her whole life. We built our own home on the farm 15 years ago; it’s very personal. This is our family legacy that they want to take away.”

When discussing the Piedmont project, Gassman experiences a range of emotions, from sadness to anger, disbelief to hopelessness. She learned about the project through a July 4 text from a neighbor who asked, “Have you heard?”

“You wake up one morning and find that your property is on a map with a giant yellow line through it, not one word from the company,” she says. “Just having those lines there cuts my property value in half.”

Her acreage includes wetlands, a pond, forest, farmland and pasture for horses. Two homes exist on the property, and Gassman rents the farmland for growing crops.

Gassman has received several certified letters from PSEG in recent months. She responded by saying she and her family want no further contact from the company and do not want anything to do with this project. And while the Public Service Commission hasn’t yet approved the project, Gassman says she feels the impact daily. Despite having dozens of “No Trespassing” signs on her property, she says PSEG representatives still show up and walk around her land. She no longer leaves her mother, who has dementia, alone, as she is terrified that company representatives will get her to sign something.

Gassman says her family plans to fight this project in every way possible.

“This is our farm and our legacy. I wouldn’t live so close to those powerlines, so I’d have to move and sell everything at half the value. And all of our memories are here. My mom has dementia. How do you move someone who only knows here and only knows this life?” Gassman says, pausing to collect herself. “It’s devastating to think that you own stuff and secure things for your family, and someone somewhere thinks they can just draw a line on a map and take your stuff. I feel like all of our rights have been taken.”

Three years ago, Charlotte Hetterick decided to switch careers. She left her job as a project manager and started farming 2 acres on her 11-acre property in Hampstead, where she has lived for 20 years.

“I just needed a change, and I wanted to get ready for retirement, and my brother and I decided to give farming a shot,” Hetterick says. “I had to throw myself into it so I could learn it before I got too old, so I’d be set up by the time I need it to benefit me in retirement.”

Hetterick and her brother both have homes on the property. Their farm, Echo Valley Farm, is organic and follows regenerative practices. They sell their goods at local farmers markets.

“For the kind of farming we do, we don’t need hundreds of acres; we’re constantly growing and seeding. We start in February and stop in October,” she says. “It’s hard. It’s fun. It’s exhausting. We have a good customer base.”

Like Gassman, Hetterick heard about the project when a neighbor texted her, “Did you hear?” After attending the first public meeting to learn more, she was furious and joined with other angry residents to create Stop MPRP. She now serves on its board.

“At first, it was a gut punch because we would lose our farm if they came through our property, so I stopped making investments and improvements in case it would be taken away,” Hetterick says. “Then I just got angry because the whole thing is wrong on so many levels. It’s disrupting lives.”

Although the proposed pathway does not cross Hetterick’s property, she says she is no less committed to fighting against the project.

“I don’t want it in my backyard, but I also don’t want it in my state. There are alternatives. There are other ways to manage power so it doesn’t destroy our land,” she says. “Everyone in the state is going to pay for this, not just people who have farms and homes destroyed. Everyone will pay for it, and we don’t get anything from it.”

She says that her experience as a farmer has deeply bonded her to her land.

“Now that I’m farming, I have a better understanding of how much time and effort goes into growing and taking care of the land and how the health of the land is tied to the health of animals, people and waterways. It’s all connected,” she says. “It’s not like you can just move and start your farm somewhere else. When we’re destroying a farm, we’re destroying a livelihood.”

Hetterick acknowledges that Maryland has to address energy needs and power supply issues. But she asserts that it must be done strategically in a way that does not include land grabs and huge rate increases for citizens who won’t benefit from it.

“Yes, Maryland needs changes,” she says, “and we need to work with legislators to make those changes so it doesn’t destroy a portion of the state in the process.”

Local Leadership United In Opposition

Local elected officials in Carroll County have taken a firm stance against the MPRP, citing its potentially devastating impact on the community, environment and property rights. Leaders have voiced unwavering opposition from the Carroll County Board of Commissioners to state legislators, underscoring the project’s far-reaching consequences.

State Sen. Christopher West (R-District 42) has raised concerns about the lack of Maryland’s influence in PJM’s planning process.

“The decision to move forward with this line was made by out-of-state entities with no regard for Maryland residents or property owners,” he states. In an email to his constituents, West points out that Marylanders would shoulder 12% of the project’s costs despite receiving no electricity from the line, which would route power from Pennsylvania’s Peach Bottom Atomic Power Station to data centers in Loudoun County, Virginia. “This is nothing more than a 70-mile extension cord benefiting Virginia at Maryland’s expense,” he argues.

West plans to introduce six pieces of legislation during the current legislative session addressing Maryland’s broader energy challenges, including increasing local power generation and revising transmission project policies. Unless action is taken, he says, Maryland faces escalating electricity costs and heightened dependence on out-of-state power sources.

State Sen. Justin Ready (R-District 5) echoed these concerns, labeling the project “a direct assault on our rural way of life.” He criticizes the proposed route for threatening farmland and properties protected by conservation easements. “Carroll County will bear the environmental and economic costs while seeing no benefits,” he says. “This is an unacceptable burden for our communities.”

Ready points out that several of the natural habitats threatened by the proposed line are home to bog turtles, a reptile protected under the U.S. Federal Endangered Species Act. He notes that the route also destroys properties that are state conservation easements, voluntarily imposed by the property owners to preserve the property in perpetuity in its natural state. The state, and in other cases county taxpayers, funded these easements.

The Carroll County Commissioners have taken a similarly firm stance.

Despite claims from PJM and PSEG that the line is critical to prevent brownouts or blackouts, local leaders remain skeptical. “It’s not clear to me that we would face those kinds of conditions anytime soon, and the calculations used to make these kinds of threats are in dispute,” Ready says.

“I have never seen any issue galvanize people to this degree in my entire life, much less my time as an elected official,” he continues. “This isn’t driven by any interest group or partisan side either. We’ve got people from all political persuasions and backgrounds united.”

What Now?

As the Maryland Public Service Commission prepares to review PSEG’s application, the MPRP has become a rallying point for Carroll County residents and their representatives. United in opposition, they argue that the project will fail to deliver the promised benefits while causing significant harm to the county’s rural character, natural landscapes and quality of life.

Yet, this project is likely just the beginning of broader challenges facing Maryland’s energy landscape. In the “Midday” podcast, Ferguson warns, “This is the tip of the iceberg for the types of electric transmission and generation that’s going to be necessary to power the modern economy here in Maryland. And if we don’t move forward, all of us are going to be facing significantly higher bills, which I don’t think anyone will tolerate.”

Carroll County’s fight highlights Marylanders’ need to educate themselves about the energy landscape and engage with their elected officials to advocate for sustainable, community-centered solutions. As proposals like the MPRP become more frequent, the decisions made now will shape Maryland’s energy future for decades to come.

The Public Service Commission is accepting public comments at www.PSC.State.MD.us/pseg-maryland-piedmont-reliability-project/.

The proposed route of the Maryland Piedmont Reliability Project cuts through many miles of Carroll County homes, farmland and businesses, plus Frederick and Baltimore counties. Proposed map from PSEG.com.

The proposed route of the Maryland Piedmont Reliability Project cuts through many miles of Carroll County homes, farmland and businesses, plus Frederick and Baltimore counties. Proposed map from PSEG.com.

Click on the map to get more details and a closer look.