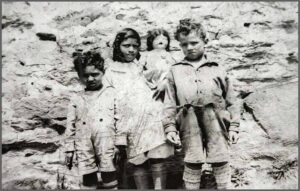

The Dorsey Family, circa 1952. Photo supplied by the Dorsey Family, First Row: Thelma, Ed, Carrie, Warren (Tom), Second Row: Clifton, Romulus, Mae (Sis), Catherine, Emerson (Wee), Third Row: Chester, Russell, Rosie, Everett, Vernon.

by Linda L. Esterson

Life on the Hill: The Dorsey Family Legacy in Early Sykesville

At the edge of Sykesville, above Main Street, sits Oklahoma Hill, an area rooted in history. It was on this hill that the legacy of the Dorsey family and its matriarch established the foundation that would propel her children and other African-Americans in the community to success in the early 1900s.

Carrie Dorsey, the daughter of slaves, was the mother of 12 children. She made sure they were fed, clothed and cared for, and she motivated them to achieve more than living disadvantaged lives on the hill. Local author Jack White chronicled the Dorsey family’s story in his 2014 book In Carrie’s Footprints, following significant input from Warren Dorsey, Carrie’s son. White and Warren Dorsey met by chance, and after developing a relationship, Warren asked if White would document his family’s story.

Carrie Dorsey, the daughter of slaves, was the mother of 12 children. She made sure they were fed, clothed and cared for, and she motivated them to achieve more than living disadvantaged lives on the hill. Local author Jack White chronicled the Dorsey family’s story in his 2014 book In Carrie’s Footprints, following significant input from Warren Dorsey, Carrie’s son. White and Warren Dorsey met by chance, and after developing a relationship, Warren asked if White would document his family’s story.

“Was his family famous for any reason? No, they weren’t,” says White. “They are just representative of the life that the people were living up there at that time. His family was the most well off of them all. They were still dirt poor.”

The book inspired town officials to rename Warfield Park, rechristening it Carrie Dorsey Park in 2018. A dedication ceremony recognized Carrie and the Dorsey family in July 2021 at the park, located about a mile from Oklahoma Hill near the entrance to the Springfield Hospital grounds.

“My mother was dedicated to moving us forward as best she could,” says Warren Dorsey, Carrie’s ninth child, who turned 101 in November. “She always told us kids that there would be a better day tomorrow, not really knowing exactly what that meant. But we’ve managed to go on, and the family proliferated into many areas and many different professions.”

Sykesville Mayor Stacy Link adds, “The park was named after his mother because of … what she was able to accomplish and offer an opportunity… constantly telling the kids to be ready for the opportunity when it arrives. She was offering them the opportunity to have the opportunity to succeed.” Link notes that the Dorseys, along with other hard-working black families during the early to mid-1900s, paved the way for future generations and the diversity that is a welcomed part of Sykesville today.

“Carrie was determined that her children find a better day,” agrees Patricia Greenwald, a former schoolteacher who directed the preservation of the Historic Sykesville Colored Schoolhouse, which all 12 children attended. “And she prepared them for that. She demanded it. She demanded excellence from them.”

Warren Dorsey was born prematurely in 1920 on the family farm. The home had no electricity, and the only heat came from the stove, fueled by the wood found on their land. He was small, hardly breathing, and Carrie’s mother, Catherine (known in the community as Aunt Kitty), delivered him, as she did his siblings and many other children on the hill. Doctors didn’t provide care for the black community at the time, so women in the area pitched in to help with the delivery and to care for the baby and pray.

With his condition so grave, Warren wasn’t named until an old acquaintance of Carrie’s family, Professor Lee, visited by chance. During Carrie’s youth, he had taught academics to many children in her community, located just five miles south of Sykesville. Professor Lee asked to name the baby Warren Gamaliel Dorsey, for the 29th president of the United States, Warren Gamaliel Harding, following his election.

During their youth, Warren reflects, it was an “unwritten rule” that all 12 children worked on the family farm on the hill, although not all at the same time. As children got older, they moved out and the family grew with additional children. The farm provided enough resources for the family to be self-sufficient. This was Ed Dorsey’s goal from the time he, Carrie and their first five children moved there in 1915.

The couple had married around 1903, when Carrie was 16, and roamed from place to place as Ed sought work. He worked on a dairy farm in Virginia, returned to Bush Park near Howard County where he was raised and later worked at Springfield Hospital as a cook. Ed quit many jobs, including from Springfield several times, over the way he and other African-Americans were treated. This fueled his desire to create his own income for the family. They settled in Sykesville on Main Street in a house behind the Harris grocery and dry goods store. Carrie did the family laundry for one of the Harris daughters in return for use of their four-room shack. Margaret Harris proved extremely generous to the Dorseys, providing shoes and clothing for the children each year.

They lived there for a while before moving up the hill, where much of the black community had settled. At one time, there were as many as 14 families on the hill, Warren says. The Dorseys bought a house on a lot of about 40 acres and built a farm.

“The farm was sufficient for us to raise our own food and just about everything we needed,” says Warren. “My father’s dream was to be self-sufficient. And in many ways, we had become that. We were able to raise a lot of what we ate.” They grew a tremendous garden — Warren recalls 200 tomato plants, for instance — and raised poultry. The expansive property also enabled the family to use its own wood for fuel, and exchange eggs and produce for staples that couldn’t be produced locally, like grains and sugar, found at the marketplace in downtown Sykesville. But the success is attributed to Carrie’s dedication.

“I often call it the Dorsey machine and she was the engineer,” Warren says. “Everybody was involved.”

Ed, Warren says, continued struggling to cope with the circumstances he was born into. Eventually, he isolated himself to keep from dealing with the reality, and Carrie and the children took over fully.

In addition to hard work, Carrie stressed education. Her children walked miles to the Old Colored Schoolhouse, which provided education for black children up to seventh grade.

“She was virtually illiterate herself, but she sat them all down each evening to do their homework,” says Greenwald, who hosts tours and talks as well as twice-weekly tutoring sessions at the restored schoolhouse. “And she checked it as they were doing it. And they didn’t realize that she couldn’t even read what they were doing. … And she insisted on manners, good dress, you know, everything that kind of set her kids apart.”

Warren remembers his mother requiring the children to adapt to being the targets of racist abuse and disrespect, teaching them to cope with the inevitable. “My mother had instructed us how to behave so that we did not be in conflict at all in the majority community,” he says. “She said, ‘Notice what people call you because you’re going to hear this a lot in your lifetime, but pay it no mind. The only thing that’s going to determine who you are and what your destiny will be throughout life is you.’”

It was her dedication to them and her dreams for them that compelled Warren and many of the other children to pursue life beyond Sykesville. Warren also cites the influence of older sister Thelma, who moved in with an aunt to attend better schools in Baltimore and earn a master’s degree from New York University. Thelma became a teacher, laying a path that many of the siblings followed.

The others who completed their schooling graduated from Robert Moton High School. They walked four miles to catch a bus in Eldersburg to get to the school, and dealt with discrimination that followed desegregation in schools. Some continued on to college. Warren moved in with Thelma and her husband in Baltimore to enroll at Morgan State College, and after six years and fighting deadly illnesses after being exposed to microbes during his research, he graduated with a degree in biology. He dreamed of pursuing a Ph.D. to help farmers via microbiological enrichment.

He, like two of his brothers, joined the Army. Afterwards, he worked as a microbiologist at Fort Detrick for decades before federal cuts to research in the early 1970s. That led to a new career: teaching. Warren enrolled at Goucher College and was the first black man to earn a master’s degree at the Towson school, according to Greenwald. He taught in Frederick, where he lived with his wife, Carolyn, and three children, and would become a school principal before retiring in 1981 at age 60.

For the last 74 years, Warren has remained in Frederick, and his children provide transportation to doctor’s appointments, to his talks back in Sykesville at the Old Schoolhouse and to family reunions, which were first held in his youth in the pool room Ed built on the farm.

Multiple generations of the Dorsey family return to Carroll County each year to gather for family reunions and share updates on their lives. They discuss the past year and their aspirations for the next. During the 2021 reunion, Warren and his sister Rosie Dorsey Hutchinson, 95, gathered with their children (Warren and late wife Catherine’s Glenn, Robin and Susan, and Rosie’s Paula with late husband Paul Hutchinson), nieces and nephews, totaling more than 70-plus Dorseys. Warren and Rosie, who lives in Baltimore, are the last remaining of the 12 Dorsey children.

Today, Oklahoma Hill is different, with simple townhouses built through the Department of Housing and Urban Development after the shacks were demolished in the 1970s. They have plumbing, electricity and air conditioning, a far cry from how the Dorsey children lived decades before, with a wood stove providing the only heat and the children sleeping three to a bed on a mattress made of straw.

“That was a distressing time for me,” Warren says regarding the destruction of his family home. “I consider that was the legacy of the family and would love to see it perpetuated. But that wasn’t to be. And just as we had with what governed our lives, you accept your reality, whatever it is and move on. And that’s what I’ve done all my life.”

Warren can hear his mother’s words as if she were alive today. “You kids did the best you could with what you had,” he says. “She used to tell us, ‘There’s gonna be a better day. I hope that what you’ve taken from your living that what I predicted for you, it has become your reality.’

“I think the success that I’ve had or the other children had could be attributed to my mother’s urging us and encouraging us by saying, ‘It’s going to be a better day tomorrow.’”